Can three trap sizes really do it all?

By Cary Rideout

Photography by Lorain Ebbett-Rideout

Every so often it’s interesting to speculate on just which three of the many modern traps we are so fortunate to have might do it all. It’s one of those questions that gets opinions flying thick and fast with points followed by counterpoints, not to mention all sorts of outlandish examples. Pure speculation, sure, and of course, who wants to be restricted to only three flavors? Still, it makes a trapper wonder … Why?

So, here’s the basic question: three traps to efficiently work a line. Sounds interesting, maybe even challenging. You would be surprised at the number of pros who keep the tool choice to just two or three, preferring to tweak their methods rather than run some of every trap size available. Long-hauler or short-liner alike, both find success with well-chosen steel that can take whatever comes along. Steel stringers all have favorites, the traps they reach for over and over with positive results. It might be a mix of styles, three alike or something bordering on mad genius. Regardless, we are creatures of habit and will use that which we feel comfortable and confident with. This can best be explained using the sports analogy of a Triple Play. But instead of bringing home all three bases, it’s about traps that can do it all and more. Can three traps perform across the board effectively, or is it just an exercise in being too frugal?

Only small stuff left in the pack basket? Think it out and work the small pan in so that furry foot hits it. Photo credit Lorain Ebbett-Rideout

Now before you sally forth, remember our choices today are influenced by regulations — and in no way am I advocating to ignore the law. Be a good citizen and run your lines to the letter of the law. Carefully read all of the regulations in your district to be sure your three-trap selection is OK with the folks in the Ranger uniforms.

Compromise and Other Forces

Old-time trappers often had their iron choices made by necessity and compromise, a troublesome pair that still rule our lives. With limited access to steel, generations of trappers made do with whatever they could scrounge. Farm boys like myself 50 years ago had all sorts of mismatched tools for the fur lines across the back 40. It was either too big or else painfully small, and always questionable in usefulness. Fur productivity with steel better used for wall-hangers is no way to begin your career but that’s how we did it. With two or, at best, three sizes, many beginners either learned the fine art of compromise or quit and went back to football.

A selection of steel for a ‘coon and mink line. Good choices for any otter snoopers, as well. Photo credit Lorain Ebbett-Rideout

But Triple Play setters are wily individuals always willing to at least try to make the available trap work. Have too big a foothold and a hot water location that begs for a set? Well, now it can be adjusted with some angling of jaws and springs. It might not look book pretty — but with one jaw raised a #3 coilspring can put the stop to a mink’s trout depredations, and many of you have done it. Sort of an emergency body grip if you can get them to hit the pan right. And don’t get all prissy over an exposed jaw because mink scent steel every day. Like I was advised by far wiser trap veteran, offer a snoop something irresistible and they will be waiting for you come the morning light.

On a canine line and all out of the big iron? OK, so think it over and examine the terrain. Most fur on land expects the walking to be rough and if a smooth path is ahead, they’ll take it unless past experience tells them different. And the extra crafty ones are another trapper’s problem, anyway. Get them steered over and onto your smaller trap pan. Don’t discount a #2 or even a #1¾, set it confident because it can work. And if using a small trap — never set solid unless it’s underwater. A light set will produce with a movable drag of brush or a dry wooden pole.

The #1 longspring has a long history on the traplines and is still a top Triple Play choice. Photo credit Lorain Ebbett-Rideout

For the water trapper, it’s even easier to compromise, as the swimmers expect to be pushing all sorts of objects aside as they move along. Guide them into a slightly smaller trap with soft wet weeds or grass — anything to control the direction. Water fur will wedge itself into some mighty cramped openings, so you can be extra aggressive here. A good Triple Play always is about compromise and creativity, two things we trappers sure have in good supply.

Big and Small

Hands down one of the wackiest three choices was a #0 longspring and a husky #4, paring with a classic #21 Blake and Lamb for anything else that volunteered. Talk about all over the place. This trio was the choice of an extremely specific setter who never felt it looked a bit odd. The #0 longspring was for the weasel he targeted, both for pelts and bounty, and yes, fur bounty was a bonus for much of the first half of the 20th century. His big steel in the form of longspring #4s worked for wet or dry land targets. After WWII, he had the opportunity to work a beaver line from the 1940s to his passing in the ’70s. He was a drown-wire man and no apologies even after the square options appeared. Hey, it worked so why switch? As fur numbers increased, he added a third trap the famous B&L #21.

Classic B&L #21 — the preferred mid-range choice for a very successful trapper. Photo credit Lorain Ebbett-Rideout

If you have never encountered this classic, you’re not alone, as it seems they were very regional in use. The #21 was touted as proper for everything from weasels up to foxes or bobcats, but was especially effective on raccoons. Maybe today we wouldn’t set this jump-style hybrid, but if you ever saw this man’s fur catch it was tough to belittle the B&L #21’s place on the line. His triple play stood him well partly because he knew the exact way to use them, and partly because of a very thorough knowledge of his furry foes — all traits we ought to emulate today.

Wirey Options

Few fur chasers are as firm in their opinions as the snare stringers. Get one talking and be ready for some strong and certain reasoning because snare failures are nothing anyone wants. One of the wirey sorts I have listened to had his own Triple Play and would brook no criticism. He’d used this set of snares for decades, both above and below the water line, and felt he’d gotten it to a point that couldn’t be improved. Very typical for a Triple Play pro.

A Triple Play of snares. On top an old-style crucible, next a water snare, and on bottom a modern canine and cat steel. Photo credit Lorain Ebbett-Rideout

He’d started out with the old-style crucible .020 used for red foxes or bobcats way back in the last century when quality wire and locks really took off. He made all of his snares, and if the crucible wire ran short he wasn’t averse to unwinding large industrial cable or coils of automobile wire that he scrounged. He liked the way the firm wire hung and hooked, especially with the slowly increasing numbers of raccoons. His light snares picked up a fair number if fishers, too, in those less strict times.

Once he got comfortable with things, what would you know but a new furbearer appeared. The first coyotes, or brush wolves, as he called them, crept over into his county by the late ’60s, requiring new methods. At the time he was still snaring bears and had plenty of stiff 19×0.025 wire. He tried to downsize it but that failed, and ended up purchasing the new 3/32 cable. Well! As he put it that tied things up and he was back in business. Still, if it looked like a fox or feline would be the only likely catch, he stuck to the smaller size wire and was pleased with his score.

Another wire situation came in the form of beaver work under the ice. Like most districts in the 1950s, he was allowed only a few tags, generally 20, and had to really hustle to find enough lodges. As a fan of the early snowmobiles, he found that hauling big #4 jump traps and tools was too much for the single-cylinder machines and went back to his wires. He set up baited poles with a string of 1/16 snares and never went back to under-ice traps, not even the square killer traps. Nope, like many Triple Play trappers, he confidently hung his snares and picked up otters along with beavers. Before the changes in regulations, he even snared marsh muskrats in tunnels. Three snares and no more. Another Triple Play!

Boxed Fur

I suppose it doesn’t surprise anyone, but with some districts reducing the trap choice to live traps, there are numerous fur chasers who have switched just to keep going. Now, right off the bat I am at best a casual cager, and set them only in farmyards or around livestock. But a professional that I know has a Triple Play of boxes that certainly qualifies. He still uses the conventional square and foothold iron, but never hesitates to set a mesh box, as he calls them. So, what does a live trap Triple Play look like? Well, the workhorse for this set of tools is the single-door 32x10x12 that handles big winter boar raccoons and keeps them stationary. With solid staking, brush cover and an inviting dark entrance, he claims some additional fur surprises such as fishers and martens. Even the occasional finicky bobcat wanders in, learning too late there is no free meal. No canines yet, but as we all know this is bound to happen sometime.

Professional ADC and full-time trapper choices. Yes, this boxed Triple Play is ‘rat ready. Photo credit Lorain Ebbett-Rideout

His backup for the perfumed folk is the 24x7x7 with a good covering sack, and recommends close quarters to keep the tails down and the chance to spray to a minimum. Personally, I never had much luck with non-spraying skunks and think it is one of those urban myths, but it might just be carelessness on my part and too much hurry. Again, the odd weasel or small ‘coon volunteers, although the larger raccoons once wedged in can come out looking like a square fur bale. Both sizes meet this trappers needs as a damage control officer and fur trapper. And to round up the trio, he reaches for wire in the form of muskrat cages. Both square and round models are familiar and make short work of big-number colonies provided you can find one these days, eh? Some nice mink are added and he claims a small otter stuffed itself in, and despite ruining the cage, it held the critter. So a larger otter-ready model is in the works in his garage. A truly boxed Triple Play!

Top Three Tally — Sort Of

And how does this humble author answer the Triple Play challenge? For me, it is not a static choice as my traplines go from wilderness to farmland changing season to season, but it basically looks like this. A powerful 8×8 killer trap backed by a strong 6×6 and finished off with an Amberg lock 3/32 snare. The first trap would answer my beaver/otter needs, and yes, a #280 is sufficient for Old Castor. The 6×6 would work the bucket brigade and the 3/32 snare would handle canines to cats, covering the farmland setting nicely.

The North Country calls for solid performers and these two killer-style traps cover plenty of bases. Then the classic #2 double longspring can guard the rocky waterways for travelers big and small. Photo credit Lorain Ebbett-Rideout

For the big Northwoods targets such as marten or fisher with no beaver work, then a tight-closing 7×7 killer trap and the slightly larger #120 models now made by some manufacturers with extra powerful springs, can handle all of the mustelid needs. In this case, the focus is narrow with many species ignored. But still, my woods line needs a third choice and the venerable old #2 longspring would be just right for mink or those muskrats that show up on rocky streams. A full-on beaver line Triple? Easy. A stout 10×10 killer trap and #1½ footholds for ‘rats, with a couple dozen coilspring #4s. Three choices can be an excellent way to focus hard and get your mind working on the limitless possibilities. So, if I went to a #2 coil with a #4 longspring and a 5×5 killer trap? Well, it’s fun to be challenged.

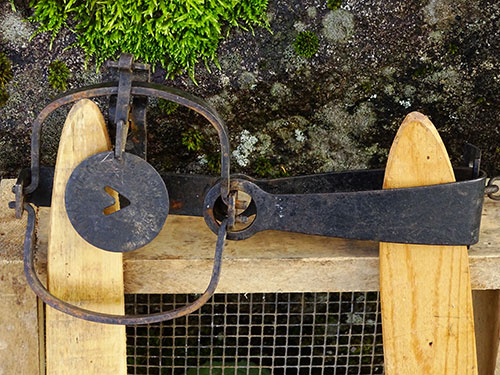

With a solid #4 longspring for water and land, a #0 longspring for weasels and a midsize #1¾ coilspring for the rest, this setup clearly explains the Triple Play idea. Photo credit Lorain Ebbett-Rideout

Any trapper who has three tools for all of their setting situations is one tough fellow to convince otherwise. They are almost always well versed in the fur targets’ habits, trap requirements and most important — have the mileage to back up what they haul out each autumn. Could they do better with a more popular choice? Who cares about popularity when you can barely keep the catch skinned! So, if the current rough times have dulled your desire, why not set yourself a new challenge and see if you can pull off a Triple Play.

Stay safe and trap fair.